A-to-I mRNA Editing in Animals : Study

Researchers from China recently reported that it’s hard to make sense of the widespread persistence of A-to-I mRNA editing in animals.

- Researchers identified 71 genes in graminearum that contain premature stop codons (UAG) in their unedited mRNA.

- These were termed PSC (premature stop codon-containing) genes.

- Deleting these genes had: No impact during asexual growth.

- But significant disruption during sexual development, proving the essentiality of A-to-I editing in these stages.

- DNA acts like a recipe book for building proteins using 20 amino acids. Each recipe (i.e., gene) is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA).

- The mRNA is then read by ribosomes to assemble proteins. The mRNA is composed of four nucleotide bases: A (adenosine), U, G, and C.

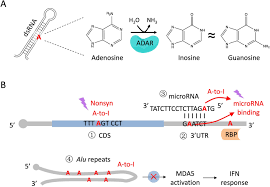

- In A-to-I mRNA editing, the adenosine (A) in mRNA is enzymatically converted into inosine (I) by proteins called ADARs (Adenosine Deaminase Acting on RNA).

- The ribosome reads inosine as guanine (G), altering the protein’s amino acid sequence post-transcriptionally, without any change in the DNA.

- A-to-I editing can change the codon identity, thereby producing a different amino acid in the resulting protein.

- This may lead to functional protein diversification and alteration in protein stability or activity.

- A major risk is misreading stop codons: A stop codon like UAG or UGA may be edited to UGG, coding for tryptophan.

- This allows the ribosome to continue protein synthesis, potentially creating abnormally long or malfunctioning proteins.